When we think about physical performance, we often imagine strength, speed or endurance. And yet, behind every squat, sprint or swing lies a deeper base: motor skillsS These skills are the building blocks of movement. From the first steps of the baby to the profitable performance of an elite athlete, motor skills determine how effectively we move, adapt and differ.

In this article we will study the basics of motor skills, the difference between a fine against rough motor skillsStages of motor development and why they are important not only for athletes but also for everyone – for adult children.

What are the motor skills?

Motor skills are learned movements that include coordination of the brain, nervous system and muscles to create purposeful actions. They are not purely instinctive; they are developed through repetition, practice and neurological adaptationS

For example:

- A child learning to catch a ball develops coordination between hands and eyes (motor skill).

- The squat technique to improve weight is refined Gross engine controlS

- A pianist who controls delicate finger movements The fine precision of the engineS

A mixture of motor skills Cognitive Processes (Planning Action) and Physical performance (muscular activation)S That is why they are at the heart of the whole movement – from basic daily activities such as walking and eating, to complex athletic performances.

A fine against rough motor skills

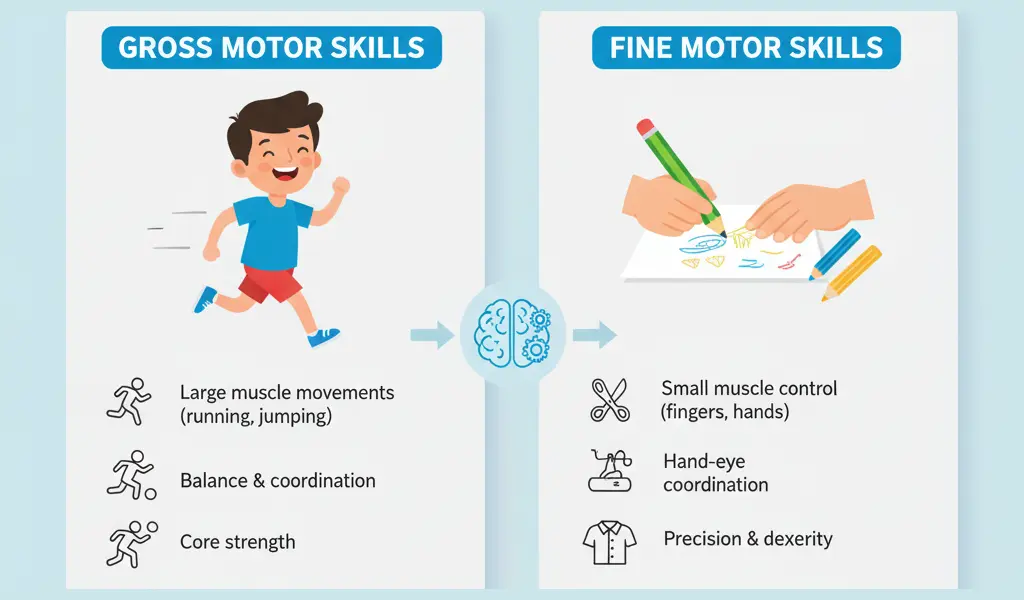

Central distinction in motor skills is a fine against rough motor skillsS

Gross motor skills

Gross motor skills include large muscle groups and movements of the whole body. These skills are essential for balance, strength, coordination and mobilityS

Examples include:

- Walking, running and jumping

- Tossing

- Performing squats or push -ups

- Swimming

Gross motor skills are crucial to athletic results and functional independence. Without a well -developed gross motor coordination, even simple tasks such as climbing stairs or maintaining balance becomes challenging.

Fine motor skills

Fine motor skills include smaller muscle groups – especially in the hands, fingers and wrists. These skills require precision, dexterity and controlS

Examples include:

- Writing or drawing

- Shirt

- Introducing a keyboard

- Controlling the power of gripping in sports (eg tennis, rock climbing)

Fine motor skills may seem less important to athletics, but they are crucial to a sport requiring precision– Archery, gymnastics, martial arts and even weight lifting, where the grip and control of the bar are essential.

Stages of engine development

Motor skills develop in a Contineum throughout lifeStarting at an early age and continuing at adulthood. Understanding these stages helps coaches, coaches and parents to support proper growth and efficiency.

1. Reflexive movements (0–1 year)

- Inadvertent responses to stimuli (GRASP Reflex, sucking on reflex).

- Voluntary Movement Foundation.

2. Rudimentary movements (0–2 years)

- A major voluntary control arises.

- Rolling, crawling, sitting, walking.

3. Phase of Main Movement (2-7 years)

- Development of basic skills: running, jumping, throwing, catching.

- Children learn models of movement through play.

4. Specialized phase of movement (7-14 years)

- Skills become sophisticated and adapted for sports or activities.

- Transition from « game » to structured training.

5. A lifelong application (14 years onwards)

- Prolonged improvement through practice and sports -specific training.

- Adults adapt the motor skills to personal goals (athletics, fitness or daily function).

- Later in life, maintaining motor skills is crucial for independence and preventing fall.

Why motor skills matter

Motor skills are not just for children or athletes – they are essential for human life. That’s why they matter:

1. Athletic presentation

- Coordination and efficiency: Athletes with better motor skills use less energy for movement.

- Reaction time: Fast motor answers determine the success in competitive environments.

- Skill: From the dribble of basketball to the performance of Olympic lifts, all athletic skills stem from motor training.

2. Daily function

- Simple activities – upholstery, driving, carrying food – relate to motor skills.

- Strong motor skills improve independence and confidence In everyday life.

3. Prevent injuries

- Poor engine control often leads to movement compensation.

- Proper coordination and stability reduce the risk of excessive injuries and falls.

4. Cognitive Health

- Motor skills and cognitive processes are tightly connected.

- Research shows that Studying new motor skills enhances brain plasticityImproving memory and problems solving.

5. Aging and longevity

- Motor skills training retains mobility, coordination and balance in adult adults.

- Prevents falls, one of the leading causes of injury in aging populations.

How to learn motor skills: Motor learning science

The acquisition of motor skills includes both brain and bodyS

Key items:

- Neuroplasticity: The brain is adapted by creating more strong neural pathways with practice.

- Feedback: External feedback (by coaches or technology) accelerates training.

- Stages of training: Cognitive (understanding of the task), associative (refining), autonomous (automatic performance).

- Repetition: Repeating skill under different conditions increases adaptability.

Use athletes and coaches Principles of Motor Training Design training sessions that improve coordination, efficiency and adaptability.

Exercises to improve motor skills

Motor skills can always develop – whether you are a child, an adult, an athlete or an adult adult.

Gross exercise for motor skills

- Stairs with agility (work with legs, coordination)

- Sprint workouts (response time, speed)

- Balance Board training (stability, proprioception)

- Power training with free weight (whole body coordination)

Exercise with fine motor skills

- Gripping strengthening (hand coordination, dexterity)

- Workouts to throw and attract a ball with small items

- Exercise with finger dexterity (piano, introduction or therapy putty)

- Precise sports practice (archery, darts, table tennis)

For adult adults

- Tai Chi (Balance, Controlled Movement)

- Walking with a variety of surfaces (coordination)

- Light resistance training (engine dial)

- Functional tasks (carrying, reaching, bending)

Motor skills in sports

Athletes are often distinguished by mastering motor skills:

- Basketball: Dribling requires a fine motor control of the fingers and the rough motor coordination for agility.

- Football: Working with a ball, balance and agility rely on precision motor skills.

- Gymnastics: Combines fine control (grip, balance) with rough motor acrobatics.

- Lifting: The perfect time and coordination of multiple joints is essential.

Even within the same sport, athletes with superb engine control are often distinguished more quickly and present themselves more consistently under pressure.

Improve motor skills through training

For coaches, coaches or persons, here are tips based on evidence:

- Prioritize the technique in front of the load – Power without coordination leads to poor engine development.

- Include variability – Practice skills in different contexts (eg dribble on different surfaces).

- Use feedback contours – Video analysis, coach adjustments or wearing technology help to improve movements.

- Progress gradually – Go from basic to complex tasks.

- Integrate cognitive challenges -Double tasks (movement + mental tasks) improve both brain and motor function.

Conclusion

Motor skills are the basis of the whole movement– From the daily activities for elite sports results. Understanding the difference between a fine against rough motor skillsRecognizing the stages of their development and their training strategically can improve efficiency, improve health and promote independence throughout life.

Whether you are an athlete who is looking for a top performance, a parent supporting the development of the child or more adult, aiming to remain active and balanced, the motor skills are central to your trip. By investing in movement and physical coordination skills, you do not only train your body-you learn your brain, resilience and long-term well-being.

Literature

- Gallahue, DL, Ozmun, JC, & Goodway, JD (2012). Motor development understanding: babies, children, adolescents, adults (7th edition). Mcgraw-Hill.

- Payne, VG, & Isaacs, LD (2017). Human engine development: Life approach (9th edition). Routledge.

- Schmidt, RA, & Lee, TD (2019). Motor training and efficiency: from principles to application (6th edition). Human kinetics.

- Haywood, KM, & Getchell, N. (2020). Development of the life expectancy (7th edition). Human kinetics.

- Clark, JE, & Metcalfe, JS (2002). Mount of motor development: metaphor. In JE Clark & Jh Humphrey (Ed.), Engine Development: Research and Reviews (Volume 2, pp. 163-190). Naspe Publications.

- Adolph, Ke, & Robinson, SR (2015). The Way to Walking: What to learn to walk tells us about development. In A. Slater & PC Quinn (Ed.), Development Psychology: Review of Classical Studies (pp. 102-120). Sage Publications.

- Barnett, LM, et al. (2009). Child possession of motor skills as a predictor of the physical activity of adolescents. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 19 (3), 267–272.

- Williams, HG, Pfeiffer, KA, O’Neill, JR, Dowda, M., McIVER, KL, BROWN, WH, & PATE, RR (2008). Motor skills and physical activity in pre -school children. Obesity, 16 (6), 1421–1426.

- Voelcker-Rechage, C., & Niemann, C. (2013). Structural and functional changes in the brain, associated with various types of physical activity throughout the period of life. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 37 (9), 2268–2295.

- World Health Organization (2019)S Guidelines for physical activity, sedentary behavior and sleep for children under 5 years of age. Geneva: Who.